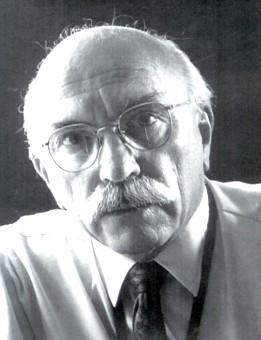

Dr. Nicholas F. Zbitnoff (1902-1987)

Excerpt from: Spirit Wrestlers: Doukhobor Pioneers’ Strategies for Living (2002): 193-196.A Passionate Medical Doctor and Keen Photographer

As ethnographer, I had the privilege of doing a tape-recorded interview with this distinguished doctor in 1978 (1). In 1990 his surviving children, Igor, Maxim, Tamara, and Anna invited me to the original home in Ukiah for a pomenki or memorial commemorating the lives and times of Doris and Nicholas Zbitnoff. Relatives from across the USA came to the commemoration and generally stayed for two full days. This included the Monaghan and Zimmerman families that stem from the mother's side of the family. The Monaghans came from Chicago where Dr. Zbitnoff first met his wife. We ate borshch and pancakes, watched slides from Dr. Zbitnoffs huge collection, and exchanged reminiscences of the deceased. See 194 photos below.

Harley Hayes, an old friend of Dr. Zbitnoff, told us how he first met the doctor in 1946 around the time that he was Head Photographer with the U.S. Government Service. When Nicholas bought the first 35-mm reflex camera, Harley followed suit and got one too. The two shared photography as a life-long passion. Harley taught Nicholas some of the fine points of photography because Harley was in charge of a prestigious photographic institution and therefore learned from his colleagues. See 194 photos below.

Nicholas revered Nature so much that it was a metaphor for his philosophy of life. He didn't speak of God as such for he didn't believe in the concept of God as heaven and hell or as anthropomorphic. Igor, his son, says that his father once told him to cultivate an interest in gardening. The gardening metaphor of planting, nurturing, and tenderly looking after your growth was a metaphor that the Doctor used over and over again with his patients.

Paradoxically, shortly before he died, Dr. Zbitnoff broke his leg when he climbed a fruit tree to prune that one last branch. He survived, but one year later he died.

Harley recalls visiting Nicholas in his darkroom where he often spent rime towards the early hours of the morning. On one such occasion, Harley noticed some slugs on the floor. He advised Nicholas to get rid of these pests. Apparently Nick responded by gently gathering the slugs into a container, taking them to the river's edge, and dumping them into the water to allow them to pursue the rest of their natural lives.

On another occasion, Nicholas apologized for stepping on the moss between the floorboards. He did not wish to hurt any living thing, human or otherwise. This was consistent with his ancestors who in 1895 burnt their firearms in a public demonstration to the world that violence and wars must cease once and for all.

Nicholas was critical of drunkenness, laziness and ignorance. A deputy sheriff who had befriended Nicholas tells the story of having to wrestle a violent and drunken man and take him into custody. He had handcuffs on when they brought him to jail where he tripped and cut his forehead. They called the hospital to say they would be bringing a prisoner in to get sewn up and heard that Dr. Zbitnoff was on call. The reaction of one of the officers was, 'Oh no, he hates cops'. They brought the prisoner to the hospital and had him strapped to a table where the doctor took a close look. Still fighting all the way, the prisoner spit a glob of phlegm on Nicholas's face. Without missing a beat the nurse handed him a towel. Rather than wipe his face, he stuffed the towel in the prisoner's mouth, then proceeded to sew up the wound without any local anesthetic.

Those who did not wish to take the effort to get educated also received criticism from Dr. Zbitnoff. For him, 'education was light to carry, yet was a powerful instrument of understanding and development in life'. The story of his going to the University of Saskatchewan was that of his stepfather and mother hitching up a wagon to a horse and driving him to Saskatoon and dumping him off there.

On politics, Nicholas was critical of hawkish and narrow politicians. Instead, in a socialist manner, he espoused the need for society to look after all of its members. All citizens ought to have full access to the fruits of its resources. The weak ought to be protected from the whims and rapacious actions of the strong.

In contrast, Harley was a classic capitalist. He believed in the free market system as the one that best provides livelihood for Americans.

This socialist/capitalist mix provided for some active and heated discussions on the appropriate political role of government in the affairs of its citizenry. The two politically opposed friends spent hours discussing politics, religion, photography and life. Sometimes this took place at Harley's residence. Other times it was in the Zbitnoff household or perhaps in Dr. Z's medical office. Dr. Zbitnoff would schedule appointments for his friend at the end of the day in order that they could pursue their favorite pastime, that of good discussion.

While Harley was never persuaded to the socialist cause, he says that he is now much more appreciative of that side of politics and overall received a better-balanced view of the socialist/capitalist spectrum. He thanks Nicholas for sharing this viewpoint with him.

There was indeed a close Doukhobor connection. Nicholas was educated at university, yet he was humble enough not to forget his Doukhobor background and his modest family roots. His family came from the Kars area of Turkey, which at the time was part of the Russian Empire. Each summer, as the opportunity allowed it, he would take his wife and children on a car trip to his home area in Blaine Lake, Saskatchewan. On the way back, he would usually stop at the Saskatchewan Doukhobor settlements in Buchanan and Kamsack, as well as points in British Columbia. Often he captured his relatives on black and white film. His home and darkroom were full of visual examples of his visits to the prairies — except that he usually failed to label these images for future generations. I found this out when I sought to identify some of his prints. See 194 photos below.

Also Nicholas pursued his interest in recording Doukhobor Family Trees. On many occasions, he took his Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder and interviewed Doukhobors on tape. He corresponded with relatives and friends, often seeking detailed information on their family connections. This data he added to his growing files. In addition he regularly read the Doukhobor publication Iskra, and therein gathered further information on family trees. His real object was to collect the definitive Doukhobor Family Tree Collection in North America.

Shortly after he died, the Mormons from Salt Lake City Archives came to see his wife and spent eight days copying his voluminous Family Tree records. This important resource is now housed in the Mormon Archives and is available to people seeking their family connections. (2)

Harley Hayes described Nicholas Zbitnoff as 'an excellent doctor'. He was often known to visit his patients at home at all times of the day or night. It didn't matter whether they were rich or poor, he treated them equally as best he could. His appointments were often generalities: 'come in tomorrow afternoon, he would say. He didn't keep an appointment book. Sometimes people would have to wait for hours to see him. And if he felt the discussion was relevant or the person needed to hear his views, a five-minute visit could easily take 45 minutes or more.

Nicholas Zbitnoff practiced medicine for 52 years, 44 of them in Ukiah. His helping attitude endeared him to his community. Known to his patients as 'Dr. Z' he was a familiar figure at all the local hospitals, but especially at Mendocino Community Hospital, where he served for a time as Chief of Staff at the request of the Board of Supervisors. He also stepped in several times to keep the hospital and outpatient clinic open, and worked in the clinic until 1982. In 1985, at the age of 83, Dr. Zbitnoff closed his Clay Street office and retired from the medical profession. In July of that year, Mendocino Community Hospital officials honored Zbitnoff for his years of service to the community by dedicating their newly constructed lounge to him. Zbitnoff was a member of the American Medical Association and the local medical society. He was a man who combined his social, political and professional lives in his medical practice.

A local photographer in Ukiah, who was present at the commemoration, described Nicholas Zbitnoff as 'a rare photographer. He forgot the technology of filming, but instead focused on the subject before him. In doing this, he had total rapport with the subject.' The results showed in his photographic efforts. The portraits had a special quality about them — a quality of direct relationship. And that is what made his portraits so 'special', according to this local photographer. See 194 photos below.

The children tell me that their father began his photographic interest first using 8 man movie film. When this medium faded, Nicholas immediately switched to coloured slides and his collection of thousands of items extends from 1949 to 1983. These included images of not only his Doukhobor visits, but also his worldwide trips across North America, Europe, Middle East, USSR, China, and South America. Later, in the 1960s, he took an interest in black and white photography and the examples in the Zbitnoff household attest to this, ass; well as the large stacks of photographs stored in his darkroom. He used a variety of cameras, most of which were still housed in a closet in his residence. These included a Leica, Pentax, Nikon, Reflex and others. With tripod, a light meter, and various lenses, he preferred using natural light. ses, he preferred using natural light.

Nicholas especially enjoyed taking photos of flowers and sunsets. There are hundreds of examples of these in his collection. When daughter Tamara and her husband Clive Adams established their Emandel Farm (3) on the River at Willits, California, Dr. Z was there often capturing images of the family and views of the scenery. In his heart, he wished to protect the natural resources of our earth and its beauty.

Their parents have influenced all the surviving Zbitnoff children. Igor (a theoretical physicist and educator) as the oldest in the family, was the first one to visit the Soviet Union. This occurred in 1961 when the US Government invited its best students to get to know the Soviet stranger. Igor was part of a US college group that visited Moscow, Kiev, and Leningrad, in what was essentially a fact-finding tour. Unfortunately, the Cold War set in and created many negative stereotypes about the Soviet people, only later to be officially mitigated with the Gorbachev-Bush Summit. (4)

In 1995 Tamara and Anna joined Igor and his brother Maxim (5) (who calls himself a 'latter day spirit wrestler' and works in construction to support his spirit wrestling habit) in a commemorative trip to Western Canada to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Burning of Arms in Tsarist Russia. Maxim produced an especially designed T-shirt commemorating the event which he took with him and distributed his message to the world. Namely:

'The Spirit Wrestlers in

three

settlements of Transcaucasia burned

their weapons because they argued there is a spark of

love, beauty and

God in every person; therefore, it is wrong to kill

another human

being. For them, a human being is not an enemy, but a

neighbour in the

process of becoming a friend.' If their father was alive,

he would have

fully approved of their bridge-building trip to Canada.

For Dr.

Nicholas

Zbitnoff the way to peace is showing it in personal

non-violent action

and commitment.

Following one of his trips to Asia Minor where he brushed over the ruins of past civilizations and sought traces of the Doukhobor philosophy, he wrote:

'... When one asks "What

does one

want of life?", the answers may be

many, but by far and large, one would not want their life

threatened

nor would it be right to threaten others. Hence, do onto

others as one

would want others to do onto you. If this is

understandable, one does

not have to invoke any kinds of beliefs or

declarations...' (23rd June

1978).

Later, in a letter to the editor of Iskra (8th September 1981: 18), he elaborated this further:

' Our youth need not worry

what

will happen to Doukhoborism. It is

universal and couched in different words. It is within you

that what

you wish it to be. "To do unto others as you would wish

others do onto

you". If we in our daily life can carry out this simple

precept,

"Doukhoborism" will continue in the hearts of Mankind.'

Notes

- This was part of one of the periodic extensive

expeditions

that

ethnographer Koozma J. Tarasoff made amongst the

Doukhobors in North

America. An earlier expedition took place in 1975 that

resulted in a

publication (Tarasoff, 1977). A later expedition was

carried out in the

summer of 1990 with Soviet ethnographer Svetlana A.

Inikova.

- The Mormons sent six microfilm reels to Mrs. Zbitnoff

as a

"Donor

Print". These are recorded as Nos. 1578631-1578636. Also

the first two

have handwritten notes. Cal 032310. [Also see the

Zbitnoff list in California

Death

Records, RootsWeb.com, and Lapshinoff

Family

History by Jonathan Kalmakoff. Search for "Nikolai

F.

Zbitnoff" for his location in the family tree.]

- Tamara, "Tam", and her husband Clive Adams operate a

children's and

family

camp called Emandal

for some 50

people outside of Willits, California. They also produce

canned fruit

and vegetables for public sale. Dr. Z's Archive is

displayed in a

a room in one of their barns, including the original

photos dispayed

here. Make arrangements to view the arichives by

contacting tamara@emandal.com.

- Later in 1988 it was Igor and his son Yury in Moscow

whom I

met in

front of the Red Square, when I was leading a tourist

group to the

USSR. They were participating in a joint US-USSR 46 km.

marathon for

peace. The object was to sensitize the public to the

fact chat people

ought to mobilize their resources to get rid of poverty

by the end of

the century.

- Maxim tells me that he, and another brother Alex,

lived in

the Ukiah

household until the completion of their high school.

Alex, a Peace

Corps volunteer in San Salvador, died in 1968 at the age

of 23, of a

gunshot wound where he was working. His friend saw him

three days

before his death; she said that he was very depressed by

what he

experienced in the country. This suicide theory is

countered by a

rumour that the CIA killed him.

Alex was active in student government while attending Ukiah High School. On his graduating year, he was student president, an honor roll student, and a life member of the California Scholastic Federation. He was instrumental in getting President Nixon to visit the school. In 1966 he graduated from the University of California in Berkeley. Some people said that he had the potential for eventually running for president of the USA. Whatever happened in San Salvador, it shocked the Zbitnoff family as well as the wider Ukiah community.

The Reverend James Jones officiated at the funeral service in Ukiah 7th July 1968. This Rev Jim Jones was the same character who later led his followers to a suicide drink in Guyana. Dr. Zbitnoff knew many of his followers as patients.

Dr. Nicholas F. Zbitnoff, self-photograph, July 1970, Ukiah, California, USA.

| 'One of my

favourite stories about my Dad', writes son Maxim

Zbitnoff, 'was told about him by Mom. It seems

there was a guy that

came in and said "Doc, I need a shot." "Well",

answered Dad, "What's

wrong with you?" "I don't know Doc, I just need a

shot." Seeing there

was no obvious thing wrong with the patient, Dad

obliged and give him a

shot, vitamins or something. A couple of months

later the guy comes

back, "Doc, I need a shot." I guess pretty soon

there was a routine

going. Every so often the guy would come in and

get a shot and go away

feeling like he was being served. 'During the year, Dad made a point of working 5-1/2 days a week on his medicine. It was only in summer that he would take off with his family for six weeks or so of holidays. It was usually a month of travel and visiting. We saw just about every National Park and major historical site in the western US and Canada. It wasn't uncommon for him to stop every few miles to get out and take a picture in some scenic areas, one of which for him was the desert. Imagine two adults and five kids driving in the desert in the middle of the summer with no air conditioning. And travel was no vacation for Mom. Not only did she take care of the kids but we brought along our own dishes and made a point to stay in motels with kitchen facilities' (Letter 23 April 2002). |

Right: Anna Zbitnoff of Ukiah and her sister Tamara Adams of Willits, California, USA reminisce while looking through slides taken by their father the late Dr Nicholas Zbitnoff.

Dr. Nicholas F. Zbitnoff shows slides at his home.

The good Doctor in his study.

Also see:

Lapshinoff Family History by Jonathan Kalmakoff. Search for "Nikolai Zbitnoff" for his location in the family tree

Memories of Blaine Lake and Area, by Dr. Nikolas Zbitnoff. 17 of his photos.

Dr. Nicholas F. Zbitnoff and His Art of PhotographyBy Koozma J. Tarasoff, December 12, 2007 |

|

| Twenty

years

have passed since Dr. Zbnitoff died. In November

2007, his son Igor

visited the parent’s home in Ukiah, California to

celebrate his sister

Таmаra Zbitnoff’s 60th birthday. There Igor discovered 22 panels of his father’s best photographic images dating back to 1919, which he offered for display on my website. The panels total 194 images, most B&W, grouped into sets of 5 to 11. Most of the images date back to 1919 and relate to his family and friends in his Canadian birthplace. Display 1 focuses on the zealots [Freedomites] who trekked from the Kootenays of BC in 1962 to Agassiz where they established a shantytown next to the Mountain Prison where their brethren were imprisoned. Display 21 featured Buchanan and Verigin pioneers in north-eastern Saskatchewan. Often the panels had some written identification which was at times hard to read. Most were signed ‘Dr. N. Zbitnoff MD.’ While most of the images were personally taken by Dr. Zbnitoff, there were a dozen or so images that were copied from other collections. Dr. Zbitnoff’s original photos covered a variety of unique images that tell the story of Doukhobor pioneering life on the Canadian prairies. These cover work on the farm, horses and farm machinery, architecture on the farm and in the town, schooling, young and old, family groups, many portraits (his specialty), grain elevators, all seasons, plaques and monuments and the classic Doukhobor Community Home in Verigin, and a close-up of log construction. As a prominent medical practitioner, Dr. Zbitnoff had the eye of an ethnographer. His curiosity led him to capture details of different families — which complimented his lifetime quest for working on the genealogy of the Doukhobors. From the displays, we can say that Dr. Zbitnoff was proud of his pictorial works on his 22 panels. When the children invited me to a Celebration of their parents in 1990, I did see a number of these images as single photos. The family lent me these which I annotated and had sent to the British Columbia Archives for copying and transferring to the Tarasoff Photo Collection on Doukhobor History. (See 75 images in the collection as temporarily numbered and annotated as 1218 to 1293.) Dr. Zbitnoff was born in the Blaine Lake district of Saskatchewan in 1902. In his youth he acquired a standard Kodak folding camera which he used to record some of the early experiences in his community. The pioneering scenes of Blaine Lake and the village he comes from are a valuable addition to the Collection. See his biography above. The Nicholas Zbitnoff Archive is on display at Emandal outside of Willits, California where Tamara resides. Make arrangements to view the arichives by contacting Tam at: tamara@emandal.com. Also see: Memories of Blaine Lake and Area, by Dr. Nikolas Zbitnoff, showing 17 more of his photos. |

Details of the Display Panels Display

1 (9

photos): Zealot village in Agassiz, BC, 1962.

Close-up of

men with beards including Dedushka Piotr

F. Slastookin. Close-up of young

girl. Display

1 (9

photos): Zealot village in Agassiz, BC, 1962.

Close-up of

men with beards including Dedushka Piotr

F. Slastookin. Close-up of young

girl.Display 2 (5 photos): 1919. Berry picking time: Small group in the field. Drinking at the spring. Picnicing. View of Nick Voikin, berrypicker. Display 3 (7 photos): 1919. At Petrofka , Blaine Lake, Saskatchewan. Views of Makaroff couple, Posnikoff’s house, barns with log and clay construction. Display 4 (9 photos). 1919. On the bank of the Saskatchewan River at Petrofka Ferry. A view of Vasil Wasilenko (non-Doukhobor?) preaching, new converts, the faithful and curious, and a young crowd.  Display

5 (9

photos): 1919. Grandma Dunia. Grandma and Grandpa.

Grandpa

Nicholas. Same and Larion.* A Zbitnoff elder man

wearing a vest. An

outdoor view of a man cutting the hair of young man

sitting on a chair. Display

5 (9

photos): 1919. Grandma Dunia. Grandma and Grandpa.

Grandpa

Nicholas. Same and Larion.* A Zbitnoff elder man

wearing a vest. An

outdoor view of a man cutting the hair of young man

sitting on a chair.Display 6 (9 photos): Grandma Dunia. Aunt Onia and Uncle Sam. Grandpa Nicholai. Edith.* Larion when he was about 100 years old. Sam Jr., Lukeria (Glyceria), Avdotia (Edith), Larion Lindsay. Display 7 (9 photos). Nice portraits of Zbitnoffs and Savenkoffs. Axenia Savenkoff. Wasil Savenkoff. Axenia Alexeivna. Wasil Gregorovich Zbitnoff (a rephotograph of a studio photo). Nastia (wife of George). Gregori (George) Gregorovich Zbitnoff (Wasil in center was his Grandfather).* Display 8 (7 photos). Avdotia Feodorovna Zbitnoff. Nicolai Gregorovich Zbitnoff. Nastia Petrovna Fedosoff. Fedia N.Zbitnoff. Family of Feodor and Praskovia Zbitnoff. Proskovia Nicholaevna Zbitnoff. Family of 5 young children.* Display 9 (6 photos). 1919. Zbitnoff and Perepelkin family. Nicolai Perepelkin family. Getting the threshing machine ready. Edith (Avdotia) and Lukeria. A threshing scene with hay racks full of sheaves.  Display 10 (6

photos). An excellent wide-angle view of Blaine Lake

town

with many people and horses. Old cars. Old airplane.

Rope pulling

contest. View of town. Four men. Display 10 (6

photos). An excellent wide-angle view of Blaine Lake

town

with many people and horses. Old cars. Old airplane.

Rope pulling

contest. View of town. Four men.Display 11 (10 photos). 1919. Mother with infant. Self portrait. Calves and chickens. Girl reads at desk. View of five children. Olga and Mother feeding calf. Display 12 (10 photos). Family shot with Model T Ford car in background. A rephotograph of one rare image with family of 12 people in front of classic sod roof house, with young man wearing a dark hat. Mother holds an infant in her arms while her daughter is beside her. Display 13 (10 photos). Reprint of classic photo of 12. Other portraits of elders. One family of three eat outdoors on a primitive table. Rephotos of portraits in studio. Display 14 (7 photos). Couples and friends of the Harolowka [Gorelovka] Group.  Display 15

(10

photos). One repeat of No. 14. Five people on a

boat.

Single man with hat. Five people at the side of a

house. A meeting of

people in the trees. Display 15

(10

photos). One repeat of No. 14. Five people on a

boat.

Single man with hat. Five people at the side of a

house. A meeting of

people in the trees.Display 16 (9 photos). Blaine Lake scenes. Axenie Podovelnikoff and infant son Freddie. Henry and Betty Podovelnikoff. Podovelnikoff home. One man plays an accordion on a balcony of a home. Close-up of baby in wooden sledge in winter. Display 17 (8 photos). Views in the town of Blaine Lake, Saskatchewan. Grain elevator. Railroad tracks. Blaine Lake High School. Teachers. Noon hour is over. At the swimming hole. Early days parking lot with horses, oxen and wagons. A baseball team. Display 18 (11 photos). 1919. Winter scenes in Blaine Lake. [Canadian Northern Railway] CN water tank. CN railway looking east with three grain elevators along side. Main Street Blaine Lake looking south. School, Catholic Church, Firehouse and Jail. Houses. Small groups of men and women. Harry and Billy Podovelnikoff with sleigh. Display 19 (9 photos in faded colour). Views of Blaine Lake and area in summer. Main Street. Water tower. Two old barns. Display 20 (9 photos). Swatter pick-up combine. Harvesting. Portrait of farmer Wasil F. Fedosoff ‘Bill’. Portrait of Fred W. Fedosoff ‘Freddie’. Six grain elevators. The Fedosoffs. Fedosoff’s farm.  Display

21 (6

photos). Saskatchewan Government plaque

commemorating

Buchanan pioneers. Mill stone monument. Classic

Doukhobor Home in Verigin

(two

views). Elder man with sunburned face in dark

clothes — an

excellent portrait showing the stress and strains of

farming. Display

21 (6

photos). Saskatchewan Government plaque

commemorating

Buchanan pioneers. Mill stone monument. Classic

Doukhobor Home in Verigin

(two

views). Elder man with sunburned face in dark

clothes — an

excellent portrait showing the stress and strains of

farming.Display 22 (9 photos). At Uncle Sam’s farm. Buildings in the rural area sowing a summer kitchen, an old granary moved from the village. Group view of five people with young child. A view of a collapsed building with Doukhobor woman in front wearing a colourful skirt. Close-up of log construction on an old barn revealing miter joints. * To identify the relatives in the Displays, see: Lapshinoff Family History by Jonathan Kalmakoff. Search for "Nikolai Zbitnoff" for his location in the family tree. |