Analysis of Peter Verigin's death on new website |

|||||||||||||||||

| On April 27,

2006 at 10 a.m., I helped launch the Doukhobor history

module for the Great Unsolved

Mysteries in Canadian History website, at the

University of Victoria, BC — "Explosion

on

the Kettle Valley Line: The Death of Peter Verigin".

And, a Doukhobor and University student, Andrei Bondoreff

(parents Gordon and Vi), was a paid researchers for this

module about Verigin. There are 13 modules. The new web site invites anyone to help solve these 13 mysteries. Special lessons are included for teachers. I was honoured to submit information for the website:

Also see 2 photos on the B.C. Lieutenant Governor's website. Official photos by Dr. Merna Forster, Department of History, University of Victoria, P.O. Box 3045, Victoria, BC V8W 3P4. All rights reserved. |

Promotion:

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

The Significance of Peter V. Verigin |

|||||||||||||||||

| As charismatic leader of

the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood, Peter V.

Verigin made two major achievements in his 22 years in

Canada. One, he united some 5000 members of his party in a manner that postponed the assimilation of his group in the midst of a British-based colonialist country that believed in kings and queens, the military forces, and the bottom line of capitalistic economy. Two, he headed the most successful communal business in North America in the early part of the 1900s. This included the construction of over 60 one-street Russian villages in Saskatchewan and Alberta, several commercial brick factories, some 80 two-story houses in the interior of British Columbia, flour mills, sawmills, cattle, horse and grain farms, and orchards that reputedly produced the best jam in Canada. With the enormous advantage of a cooperative enterprise, the group was able to quickly leave horse, oxen and human power for steam tractors, binders and combines. As well the members were able to get contract work in constructing railway beds and highways at good prices. (Don’t forget — these people came to Canada with practically nothing.) Culturally, Peter V. Verigin’s influence allowed for the preservation of the Russian language, singing, costumes, and architecture. His death in an unsolved tragedy in 1924 was shocking. Some 7,000 people including many non-Doukhobors came out to pay him respects. |

The episode focuses on the

Doukhobors who in the 1900s posed a threat to North

American capitalism. Because of their success, neighbors

got jealous and sought government assistance in curtailing

Doukhobor ingenuity resulting in two major land losses in

1907 ($11 million or $222,000 US in today’s value) and

1938 ($6 million or $121,000 US in today’s value). The

extremists known as Sons of Freedom or zealots took

advantage of the Doukhobor name for their own purposes as

did the media. Having arrived in Canada from Russian exile in 1902, Verigin was looked on by many as a martyr for a cause — almost as a God. There were a growing number of Doukhobors who were leaving the commune as independent farmers. They saw Verigin as elitist, dictatorial and one who transgressed the principle of equality. And there were extremists with an anarchistic spirit who were not satisfied with their new land and the pressures to purchase land individually. Verigin tried unsuccessfully to unite all. Also he did not encourage public school education for fear of assimilation and losing control of the group. The Independents continued to prosper on their own merits even as Verigin sought to exclude them from membership in the Doukhobor family. In our current age of fear and power politics, it is important to keep independent thought alive and well. The opening of the Unsolved Mysteries module is an opportunity to question our common sense and test things out in our own experience. As inquiring students and scholars, our task is to deepen our focus and explore all the possible questions and facts concerning the mysterious tragic explosion of 1924. Enjoy the Socratic quest! |

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| The place was

an isolated rocky mountain road one mile south of from Farron, British

Columbia, an isolated train watering stop. The time

was 12:55 a.m., the 29th of October, 1924. The great steam

train came to a sudden halt as its First Class Coach burst

into flames. This doomed Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR)

Coach on Train 11 carried 21 passengers including two

Sikhs, a new Member of the Legislative Assembly for Grand

Forks — John McKie, and several Doukhobors with their

leader Peter V. Verigin. The explosion was horrific. It ripped off the roof of the Coach, took out one side, and greatly damaged the other, as a fire soon consumed the remains. Nine people were injured and nine were killed some beyond recognition. Many of their parts were scattered on the lightly snowy ground of the railway bed. For the history buff, this horror has all the elements of a classic Agatha Christie mystery. There were bodies and there were motives. For over 80 years, neither the CPR nor the police have come close to solving it. Many of its records were removed from public view until recently. With your Sherlock Holme's cloak and your inquiring attitude, let's unravel some of the key elements of this almost century-old mystery. The media has mainly focussed on one victim: the 65-year-old Peter V. Verigin, the charismatic President of the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood (CCUB), a group of Russian dissidents known as the Doukhobors. As these 'Spirit-Wrestlers' arrived in British Columbia in 1908, they formed several communal settlements in the Kootenay and Boundary districts. With their co-operative and hard work ethic, the Doukhobors created the most successful communal enterprise in North America. Because of their belief in the Spirit of God Within, Doukhobors refused to participate in war. For the same reason, they considered themselves spiritual in the sense of doing good, and saw no need for an intermediary church. In British Columbia, they successfully lobbied against military training in public schools, but encountered problems with the school curriculum. Peter Verigin feared education would prepare his flock to become cannon fodder. Fear of citizenship was the main reason why Verigin brought his followers to the wilderness of British Columbia from the Saskatchewan prairies where the group had initially settled as new migrants from Russia in 1899. Peter arrived in Canada in 1902 following 15 years of exile in Siberia for his role as leader of the dissidents in the Caucasus. Mixed farming, flourmills, and brick factories allowed the enterprise to prosper in Saskatchewan, but problems arose when a new Minister of the Interior (Frank Oliver) reneged Canada's promise of allowing communal settlement. An ultimatum in June 1907 was pitched in terms of becoming citizens and signing for land individually. Reverend John McDougall, who earlier cajoled the Indians to sign its treaties, was hired to visit the villages — and he recommended their breakup. Two-thirds of the Doukhobors obeyed Verigin and moved to the interior of B.C. where private ownership allowed for temporary internal control. One third of the group remained in Saskatchewan and signed for their Homesteads; they became Independents because they did not share Verigin's dictates and saw room for individual initiative. In the 1920s the mood of the country was a fear of Communism, when foreigners were suspect, and when repressive laws such as the 1914 Community Regulation Act in B.C. allowed for draconian invasion of communal groups. Also it led to the denial of the voting by the Doukhobors, Hutterites, and Mennonites. In 1938, the Doukhobor Community enterprise lost $6 million of its assets for failure to pay a debt of $300,000 — which the BC Government paid for and then broke up the communal real estate with vengeance. The Russian Doukhobor pioneering experience in Canada in the early 1900s was a laboratory for accommodation and conflict. They accommodated when they learned the English language and culture, built villages and businesses, but clashed when they successfully competed with Western businesses and political interests. Peter V. Verigin, as chief CEO of the Doukhobor commune, had a love hate-relationship in Canada. Most, but not all, of the Doukhobors saw Verigin as a great spiritual martyr, teacher, reformer and builder. Their self-sufficient communal structure allowed for the development of their own sawmills, their own brick factories, elevators to store grain and flour mills to grind them, factories for the processing of fruits and jams, and their own wholesale and retail stores for storage and distribution. At the same time, one-third of the Doukhobors rejected Verigin's 'spiritual' status as being illegitimate; and while these Independents fully retained the core pacifism of the group, they sought a more democratic organization, yet accommodated as best they could through education and businesses in Saskatchewan where the provincial administrators were more tolerant to the multicultural mix of new migrants. The government of the day in British Columbia was more centralists of the colonial British type. It stepped up the demands that the Community Doukhobors must attend government schools and become assimilated into the narrow nationalism and patriotism of its militaristic curriculum. At the same time, local merchants and businessmen petitioned the government that the Doukhobor communal structure was a threat to the established order of things and was an unwanted element in the area. Moreover, the veteran soldiers opposed the Doukhobors as a whole because, as total pacifists, they did not take part wars. One of the branches in B.C. petitioned the government to take away all the lands held by the Doukhobor Community and give them over to returned soldiers. Thankfully this did not take place. When the tragic death of the head of the Doukhobor commune did take place in 1924, the event crystallized the feelings of love-hate in western Canada. For over two-thirds of the Doukhobors, Peter Verigin was the main source of inspiration to them and their way of life. Its members interpreted the violent death as a tragedy probably caused by some government conspiracy to get rid of their head. They recalled the 1907 breach of faith in Saskatchewan when the new Minister of the Interior changed the rules of the game and disallowed communal ownership. Now, with the death of their leader, they were more suspicious than ever on the motives of provincial administrators. The local businessmen were glad to have forcefully eliminated a competitor in their midst. For local Doukhobors, however, it became obvious that merchants could not be trusted because their bottom-line was primarily to win at all costs even if it meant wiping out a competitor. After the tragic explosion, Peter V. Verigin became a rocky precipice in Brilliant, B.C. The monument had the stature of a site for a king and in no way resembled the simple grave of their mentor Lev N. Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana. The special status, like an icon, contradicted the Doukhobor notion of equality — and this action began to enlarge the gap between the Community people and the Independents. |

For the

Doukhobors, Verigin's death marked the decline of the

Community enterprise. The fear of assimilation accelerated

as zealotry began to rise. Zealots, with their extremist

agenda, began to hijack the Doukhobor name by claiming to

speak for the whole. Main stream Doukhobors were

embarrassed by their violent and sensationalistic ways

which was not part of the Doukhobor way; some even changed

their names. With no central head to look after the

enterprise, the economy began to suffer as monies spent

were at times not transparent and justifiable, and advice

from experts was not listened to. The Community membership

declined sharply in the 1930s. The impact of the explosion on Canadian society had a negative effect on the Doukhobors. The authorities and the CPR withheld the police documents for 50 years indicating a hidden suspicion about the whole affair. The media, in turn, continued to create its own social opinion by hijacking the information as if they were the source of all the truth. In the 1960s, sensational writer Simma Holt wrote about the Doukhobors as if they were zealots and Communists in disguise. At the end of the 1930s, the government broke up the Community enterprise and took away Doukhobor lands worth $6 million in British Columbia. Later, in the 1950s, B.C. authorities forcibly took away 170 children from their parents for failure to send their children to school, thereby creating the infamous New Denver School. The public was shocked by the explosion, as it was by the acts of terrorism that periodically swept the idyllic Kootenays of B.C., yet in the end many people were happy that the crucible of assimilation was working in grinding out the impurities within. The bad feelings persisted for many generations, right up to the present time. Especially, the clash of interests has had a direct bearing on the nature of democracy. How healthy is an avowed democratic state, when it does not allow dissent? Would it not have been useful for North American capitalism to allow communal structures to compete with it? The grand experiment would have shown that society could be enriched when capitalistic and communal enterprises work together. Is that not so? Instead, today many people believe that these two structures are incompatible. Here, then, was a lost opportunity to learn from the wisdom of East-West bridge-building in creating a better world. It was in this paranoiac atmosphere that the October 1924 explosion took place. The motives include:

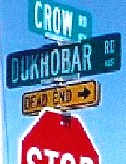

Dukhobar Road sign, 7

miles west of Eugene, Oregon. Peter P. Verigin sold

this property because he was not interested in pursuing a

remote colony there, but some Doukhobors stayed in Oregon.

See "Doukhobors

in

the 1930 United States Federal Census" by Jonathan

Kalmaloff showing 21 households at 10 locations in 6

adjacent counties in the state of Oregon, USA. This photo

was taken facing northeast at the southwest

intersection

of Crow and Dukhobar Roads, where Dukhobar Road runs

straight north and south. Photo by Larry A. Ewashen,

Director of the Doukhbor Village

Museum, Summer 2005. Click on photo for larger view. Dukhobar Road sign, 7

miles west of Eugene, Oregon. Peter P. Verigin sold

this property because he was not interested in pursuing a

remote colony there, but some Doukhobors stayed in Oregon.

See "Doukhobors

in

the 1930 United States Federal Census" by Jonathan

Kalmaloff showing 21 households at 10 locations in 6

adjacent counties in the state of Oregon, USA. This photo

was taken facing northeast at the southwest

intersection

of Crow and Dukhobar Roads, where Dukhobar Road runs

straight north and south. Photo by Larry A. Ewashen,

Director of the Doukhbor Village

Museum, Summer 2005. Click on photo for larger view.

Update (June 2015): Oregon’s Doukhobors: The Hidden History of a Russian Religious Sect’s Attempts to Found Colonies in the Beaver State, by Ron Verzuh, BC Studies, no. 180, Winter 2013/14. References

|

||||||||||||||||