Trying to Recapture Russian Emigres' Life in MexicoThe few descendants of a religious sect that fled czar's empire 100 years ago now put faith in trading on heritage to keep their ancestry alive.By Jessica Garrison — Los Angeles Times — (Home

Edition) December 1, 2002 — Page B1 Living Among Ghosts Brings a Strange PeaceFRANCISCO ZARCO — Baja California — After he retired from the mattress factory in Vernon, after his children grew up and attained happy American lives, Gabriel Kachirisky moved back to Mexico and turned his life into a museum exhibit.[The original colony was named "Colonia Russia de Guadalupe" — "The Russian Colony of Guadalupe." After Mexicans took much of the land in the 1960s the name was changed to "Francisco Zarco" in 1962, but the name of the valley remains Guadalupe. See Mohoff * pages 185-6. "Francisco Zarco" is the name of the store-post office-bus stop near the highway about 3 miles from the Russian colony.] He began sticking little labels on half the possessions in his

house.

He went back to the dilapidated church that his parents helped build,

restoring

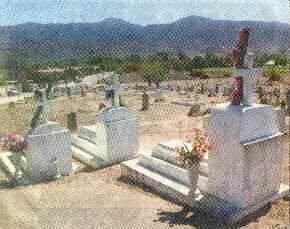

it. He even went to the cemetery, pulling weeds from the forgotten

headstones,

lettered in Cyrillic.

But years ago, squatters came and took their land. Now, villagers say, fewer than 20 remain who claim "pure Russian blood." Kachirisky and a handful of others have taken it upon themselves to keep alive memories of that way of life and a past that has all but slipped away. The Jumpers Molokans have gone into the heritage business. They greet the tourist buses that come over the bumpy road from Ensenada. They nurture and scrupulously maintain two museums, right across an unpaved road from each other. And they operate many mom-and-pop enterprises, including one run by Kachirisky. For Kachirisky and others, it is something. But it's small

solace, given

the loss of the idyllic community of their memories. And the museums

have

not always smoothed the path into the future-sometimes inflaming local

debate over who owns the past, who has a right to claim it and make

money

off it from tourists.

The new settlers consecrated a church. Every Sunday, they came to worship in the simple wood room of plain white boards and softly filtered light. They stayed for hours, drinking tea and eating borscht.

The

men

wore high-neck shirts and the women covered their heads with scarves,

just

like their ancestors. And though they learned Spanish, they spoke

Russian

to each other.

The Jumpers Molokans pleaded with them. They showed a signed proclamation from Mexican President Porfirio Diaz, granting their rights to the land. "They didn't consider you a Mexican citizen," said George Mohoff,* who was born and raised in the Guadalupe Valley, but now lives in Los Angeles County. "They said, 'Why do you have so much and we have so little?' " But the Jumpers Molokans were pacifists, unwilling to use guns and fists to hold on to their land. The settlers kept coming, and the Jumpers Molokans "were left with broken hearts," Mohoff said. By the early 1960s, the minister — and formal Sunday church services — had disappeared. Kachirisky was born here in the Guadalupe Valley. But he and his wife became part of the exodus, moving in the early 1960s to Pico Rivera in the Los Angeles suburbs. He stayed there 27 years. The little English he learned in America still comes out in a gruff voice heavily accented with Russian. But his Spanish has no accent at all, and Kachirisky and his wife transformed themselves into Angelenos, like any other immigrants from Mexico. He and his wife joined a Pentecostal church, put their kids in school and went to baseball games. They went back to the Guadalupe Valley only for visits. But by the late 1980s, a change in management had left Kachirisky unhappy at the mattress factory where he worked. He cashed in the equity in his home and returned to the Guadalupe Valley. About the same time, a burgeoning eco-tourist trade brought visitors and museum money to the valley. For a while, it looked like this would bring the community back together — although many had stopped practicing the religion. The Russians collaborated to put together the first museum in 1991. They rummaged in closets and storage spaces, and came up with a vast collection of dresses, photographs and samovars. They helped reconstruct a town map, showing where everyone had lived. Children even began learning Russian. [That map was constructed by George Mohoff, drawn by Andrei Conovaloff, and is included in Mohoff's book.*] But in 1998, a dispute over how the museum was being run led its director — a Mexican married into a Russian family — to quit and establish a competing museum. It is directly across the road from the first. Though their exhibits are substantially the same — photos, maps, bright Russian dresses and samovars — many townspeople insist there are serious differences between them. But those tend to have more to do with who put the museums together and how they profit. [See museum photos by Grishka Bolderoff.] Michael Wilken, an anthropologist [from San Diego] who leads tours through the valley, said he believes the dispute stems from differing perceptions of who has a right to claim the treasured past. "Whenever I hear the argument, it seems to be that 'So and so is making all kinds of money off this,' and 'They're not really into it for the right reasons,' " said Wilken, who said he has not taken sides in the fight. Catering to Tourists "People can have conflicts," said Julie Bendimez, director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Baja California. Her institution helped found the first museum and continues to fund it. "I don't want to continue the war between them," she said, "but that's how it has evolved." Bendimez said she thinks the two museums "complement each other." With the museums came busloads of tourists and students — up to 10,000 a year. Soon, individual townspeople began catering to the tourist trade. Maria Samaduroff got a tourist certificate and, with her daughter, serves schoolchildren cheese and lectures in her backyard. And then there is Kachirisky, who has turned himself into the town's one-man curator. It started with displaying his possessions and serving tourists blintzes. Then, he turned his attention to the church, built in 1950. The roof had collapsed, and rainwater had poured down the walls and the floors. Somehow, the Bibles were spared the mildew and rot, but almost everything else was damaged. Kachirisky spent thousands of dollars and hours of labor,

painstakingly

putting the church back the way it was. [To save the property from complete ruin, Kachirisky proposed to church members who moved to California that he be given official permission to care for the church and cemetery at his own expense so the building could be used by local residents, Russian and non-Russian, for Christian purposes. Former members in California agreed with the proposal, but before Kachirsky could improve the property he had to get this permission in writting to show to the Mexican officials. George Mohoff wrote up and circulated a letter of permission which was signed by 18 families in Caliofornia, nearly all the surviving former members in the US. A few months after Kachirsky started working on the building, a funeral was held, attended by many from California, including Mohoff. Mohoff's were very impressed by the renovation and cleanliness of the church building and cemetery. They highly praised Kachirsky for his initiative. NOTE: Previously I posted a contrary comment about California members collecting money to hire Kachirisky. I got the story wrong, for which I appoligize. It was "signatures" that were colleceted, not "money". Thanks to Andrew Garibay, grandson of Kachirisky for pointing this out to me.] Dozens of teapots and hundreds of teacups sit on a musty shelf, unused since 1960. Alongside, sugar cubes rest patiently in their pink box, as they have for four decades. [I'm also told that dozens of former residents and guests returned about in 2000 to bury an elder lady, and the church was used for a full traditional funeral and meal.] "Before, when you went on Sunday, it was so happy," he said. "So much life ... the boys and girls singing. Now when I come here, I just want to cry." In his house, Kachirisky flips on his television and pops in a home movie of a wedding held in 1939. The sound of dozens of voices singing the psalms in Russian fills his little room. His wife gazes at him fondly as he begins to sway back and forth, singing softly to himself in Russian. He points out faces of those who still live in town, people he doesn't speak to much these days. When the movie ends, he reaches over to the VCR and hits play a second time, his stiff 70-year-old body swaying back and forth, his voice lifting again with the voices of the past. *[Mohoff, George W., et.al. The Russian Colony of Guadalupe: Molokans in Mexico. 1995.] |