Scientist: Prairie dogs 'talk'Chattering critters have own language, research suggestsTania Soussan -- Albuquerque Journal -- Nov 26, 2004 -- Edited for The Arizona Republic, Dec. 4 , 2004Based on a February article. Also see the Dec. 13 Editorial in The Arizona Republic discussing this article. Also see "Prairie Dog Communication", a collection of his articles. |

|

| ALBUQUERQUE --

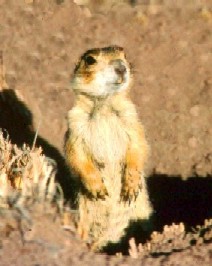

Prairie dogs, those little pups popping in and out of holes on vacant

lots and rural rangeland, are talking up a storm. They have different "words" for tall human in yellow shirt, short human in green shirt, coyote, deer, red-tailed hawk and many other creatures. They can even coin new terms for things they've never seen before, independently coming up with the same calls or words, according to Con Slobodchikoff, a Northern Arizona University biology professor and prairie dog linguist.  ["The world's expert on prairie dog

communication", Dr. Con Slobodchikoff, was raised in

San

Francisco of Russian-born parents. His wife, Anne

Slobodchikoff, is NAU's Russian

and French language professor, and advisor for the NAU Russian Culture

Club.] ["The world's expert on prairie dog

communication", Dr. Con Slobodchikoff, was raised in

San

Francisco of Russian-born parents. His wife, Anne

Slobodchikoff, is NAU's Russian

and French language professor, and advisor for the NAU Russian Culture

Club.]Prairie dogs of the Gunnison's species, which Slobodchikoff has studied, speak different dialects in Grants and Taos, N.M.; Flagstaff; and Monarch Pass, Colo., but they would likely understand one another, the professor says. "So far, I think we are showing the most sophisticated communication system that anyone has shown in animals," Slobodchikoff said in a telephone interview. Slobodchikoff has spent the past two decades studying prairie dogs and their calls, mostly in Arizona, but also in New Mexico and Colorado. He has published numerous papers on the subject in scientific journals. Prairie dog chatter is variously described by observers as a series of yips, high-pitched barks or eeks. And most scientists think prairie dogs — along with whales, chimps, domestic cats and all other animals — simply make sounds that reflect their inner condition. That means all they're saying are things like "ouch" or "hungry" or "eek." But Slobodchikoff said he believes prairie dogs are communicating detailed information to one another about what animals are showing up in their colonies, and maybe even gossiping. "Prairie dogs have what we call social chatters," he said, describing the noises the dogs make while feeding. "It could mean 'Do you know whose burrow Joe was in last night?' or it could mean 'Chitter chatter chitter,' '' Slobodchikoff said. Five tests of language Linguists have set five criteria that must be met for something to qualify as language: It must contain words with abstract meanings; possess syntax in which the order of words is part of their meaning; have the ability to coin new words; be composed of smaller elements; and use words separated in space and time from what they represent. "I've been chipping away at all of these," Slobodchikoff said. He and his students have done work in the field and in a laboratory. With digital recorders, they record the calls prairie dogs make as they see different creatures — people, dogs of different sizes and with different coat colors, hawks, elk. Then, they analyze the sounds using a computer that dissects the underlying structure and creates a sonogram, or visual representation of the sound. Sophisticated computer analysis later identifies the similarities and differences. |

The prairie dogs have calls for various predators but

also for elk,

deer, antelope and cows. The prairie dogs have calls for various predators but

also for elk,

deer, antelope and cows."It's as if they're trying to inform one another what's out there," Slobodchikoff said. He said he has recorded at least 20 "words." Some of those words or calls were created by the prairie dogs when they saw something for the first time. Four prairie dogs in his lab were shown a great-horned owl and European ferret, two animals they had likely not seen before, if only because the owls are mostly nocturnal and this kind of ferret is foreign. The prairie dogs independently came up with the same new calls. In the field, black plywood cutouts showing the silhouette of a coyote, a skunk and an oval shape were randomly run along a wire through the prairie dog colony. "There are no black ovals running around out there, and yet they all had the same word for black oval," Slobodchikoff said. He guesses the prairie dogs are genetically programmed with some vocabulary and the ability to describe things. Reacting to recording Slobodchikoff has also played back a recorded prairie dog alarm call for coyote in a prairie dog colony when no coyote was around. The prairie dogs had the same escape response as they did when the predator was really there. "There's no coyote present, but the prairie dogs hear this and they say, 'Oh, coyote. Better hide,' " he said. Computer analysis has been able to break down some prairie dog calls into different components, suggesting the critters have yet another element of a real language. "We're chipping away with this at the idea that animals don't have language," Slobodchikoff said. Whales, dolphins and chimps come to mind in discussions of animal language, but scientists have not yet been able to decipher what their sounds and gestures mean. And efforts like teaching chimps sign language are back-door approaches to the question of animal languages, Slobodchikoff said. So what's next for a biologist with a $1,000-a-year research budget facing the skepticism of the scientific community? Slobodchikoff wants to start working with other animals, perhaps getting researchers to share recordings of whale sounds and the actions that go with them or trying to figure out the more than 125 vocalizations that pet cats make. And he can envision a day not too far off when people can buy a translator box that will allow them to understand that Fido's bark means "I want to go out, stupid" or that Fluffy is meowing "No, I want the tuna today"— and to answer back. "That's a possibility, at least down the road," Slobodchikoff said. |