By: Jules F. LEVIN

and Steven E. MERRITT, University of California, Riverside (UCR) UPDATED Oct.

2007: After

teaching

college for ~33 years, Dr. Levin retired

from UCR in 2003 with the title: Professor Emeritus of Linguistics and

Russian (E-mail: jules.levin@ucr.edu

). He got his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D.

at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He joined

UCR in 1969 as a Professor, Comparative

Literature and Foreign Languages, Department of Russian. He specialized

in Baltic languages, Russian and Lithuanian. He wrote at least

one book In the Realm of Slavic

Philology (1974) and several

articles, including "Stressing Freely in

Lithuanian and Russian" (1994), and "On Hennig's Prussian Dictionary,"

In the Realm of Slavic Philology 2002 . UPDATED Oct.

2010: Dr Levin did not object to these comments, but he requested

that this text in red font and links be placed in a sidebar to remove

it from his original article. But placing the comments and links within

the text is less confusing and conforms to the purpose of this web site

to clarify understanding about Russian sectarian Molokane and Pryguny. This article is entirely

about a book used by a

faction of congregations who separated from Pryguny, who separated from

Molokane. This new faith solidified in America in the 1910s and

confusingly claims to be the true Molokan faith while rejecting both

the Prygun and Molokan faiths. Since it is defined solely by it's use

of the Book of the Sun : Spirit and

Life (S&L) for worship,

as a third-testament to the Bible, the congregants can be empirically

described as "S&L-users". Some call themselves Maksimisty,

followers of Maksim G. Rudomiotkin. See: Song and Holiday Taxonomy of

Molokane and Pryguny. Though S&L-users are instructed that

exposing their

exclusive faith, like this article does, to the non-believers (infidels, ninashi) is

mistreatment of a sacred object (sacrilage), some are

intrigued that their mystical images were examined by scholars with

respect and enlightenment. For Biblical passages,

use the

Russian Bible, or the

Douay-Rheims English Bible translation which almost matches the

Russian Bible. Single passage links below are to the Online Parallel

Bible web site.

Introduction The Pryguny Molokans are a religious group which arose as an outgrowth of the sectarian movement in Russia during the 17th Century. Broadly classified as a Pentecostal sect, they believe that the inspiration of the Holy Spirit is the final authority in all matters of faith. While they believe in the trinity, the Holy Spirit is the prime force in Prygun and S&L-user Molokan spiritual experience. The Pryguny and S&L-users Molokans believe in the gifts of the Holy Spirit described by Paul in First Corinthians, including healing prophecy, and speaking in tongues (glossolalia). They read the Old Testament, as well as the New, and observe most of the Mosaic dietary laws. The Russian sectarians Molokans are iconoclastic, and do not venerate Mary or the saints. Reformation

iconoclasm appeared in Russia as the Ikonobors from which

emerged sectarian "milk-drinkers", molokane.

In

the late 1700s, after merging with Sabbatarians, Molokans divided

into Saturday Molokans (Subbotniki) and Sunday Molokans (Voskreseniki).

In

1833

in

New

Russia, Molokans

were influenced by the neighboring Mennonite

separatists who

recently immigrated to the Molochna

Colony. The most zealous Brethren (Hόpfer, jumpers) and Molokans

shared their spiritual

dance and Holy

kiss. Begining in the 1840s, many sectarians and Mennonites were

relocated to the Caucasus where the

estatic religious jumping

continuted. The writings of Rudometkin hold a special and revered place among the Pryguny Molokans. A charismatic leader and preacher, he came to regard himself and to be regarded as a prophet, if not another messiah. After, incarceration, Rudometkin continued to communicate secretly with his followers. Despite imprisonment, he was able to compose a collection of religious writings regarded by both himself and his followers as a work of divine inspiration. The writings are filled with long passages from the Bible, yet S&L-user Molokan tradition suggests that Rudometkin was denied the scriptures during his confinement. The original manuscripts are reported to have been very small, almost requiring a magnifying glass to read (Pivovaroff 1976:32). According to S&L-user Molokan oral tradition, they were penned in an ink which is variously described as being made from soot mixed with water, or even Maksim Gavrilovich's own blood (Moore 1983:150). Smuggled out of the places of his imprisonment, they were secretly circulated among the faithful. Later, during the exodus from Russia, the original writings were brought into the United States [examined in Arizona] concealed within loaves of baked bread. The text of the manuscripts was published by the Prygun Molokan

community in Los Angeles, first in 1915 (Kamen'

Gorlion), and then in 1928 (Bozhestvennyja

Izrechenija). Both books were published under a series title Dux i

Zhizn' 'Spirit and

Life' which has now given its name to

these publications. The new Dukh i zhizn', a new prayerbook and a new song book

were placed next to the

Bible on the altar tables

of all Prygun congregations in the US and

Mexico by prophets with instructions to obey the new rituals (novye obriad). This transformed those congregations

into a new faith, "S&L-users", who rejected both the Molokan and

Prygun faiths. Though many tolerated the changes, most in the US

eventually abandoned this new faith due to this book and Russian

language services. In the 1930s, the new books were sent to Pryguny in the Soviet Union

and Turkey (Kars

oblast) where some congregations similarly used them for services. Rudometkin's original manuscripts contained many drawings and diagrams that were often virtually embedded within the text itself. The 1915 edition included four of Rudometkin's illustrations, apparently redrawn by an artist with some professional experience. The 1928 edition, however, included photoengraved reproductions of twelve different pages (nine of which feature diagrams or drawings) from Rudometkin's original manuscripts. Since it would be impossible to discuss all of Rudometkin's illustrations in a paper of this length, our discussion will be limited to only four of the reproductions from the 1928 edition and two examples of "professional" renderings from the 1915 edition. All the Rudometkin material awaits a much more extensive treatment than is possible here, so we will not be able to fully explicate the symbolism of these drawings. There is also a 1947 edition of Dux i Zhizn', which we have not yet seen, as well as an English translation by Pivovaroff published in Australia in 1976. We have used the latter publication for all of the English translations of the text and we have employed the same citational conventions (listing text by book, chapter, and verse) used by the S&L-users Molokans when noting particular passages. The English translations of the Russian text in Rudometkin's manuscript drawings are, however, our own. In general Rudometkin's writings draw upon the New Testament Revelations of John, and on one of John's primary sources, the Messianic and apocalyptic sections of Isaiah. In a sense, the work of Maksim Gavrilovich Rudometkin is yet another spin on this material John's Revelations is a reworking of material from Isaiah, while Rudometkin's writings are a reworking of both, in which he projects himself as a prophet into the revelation (as John had done before him). II. The drawings The first of Rudometkin's illustrations that we will discuss individually is Figure 1, above. Avoiding the obvious interpretation that the drawing may evoke [phallic symbol], this design depicts a palm tree. The trunk is a simple line drawing with palm fronds formed by a line of text. The latter element is a metastable figure, perceived now as written message, now as a canopy (Gandelman 1979:83ff). The text immediately below the drawing relates that "This pillared palm tree, anointed in oil and eternally embedded in stone, is positioned at the head of Zion; which is Christ and His true Spirit" (M.G. 14; 9:1). At the base of the drawing is a horizontal, rectangular shaped area containing the words "the Lord is my rock." Here, Rudometkin refers back to Isaiah 44:8, "Is there a God or any rock besides me?" A pillar rises from this base and the text contained within it reads "the heavenly date palm. " On top of the pillar is a triangle with the word "God" set at its center. The curving line of text above it reads "the canopy of this pillar is my spiritual protector," and iconically represents the spreading fronds of a palm. The significance of this drawing is set forth in an enigmatic passage that occurs later in Dux i Zhizn', where Rudometkin writes that "I am the anointed pillar that stands permanently on the rock of Zion, and I am the stairway into the seven heavens, by which all the prayers of the holy ones forever ascend and descend! Similarly on earth, I am the white horse; and always upon me rides the Lord of lords and the King of kings! Yea in truth for I do not lie!" (M.G. 14; 9:31-33). As is typical with Rudometkin, the first part of the quotation utilizes the metaphor of the Lord as rock that frequently occurs in Isaiah, while the second part refers to the Wielder of the Iron Scepter described in Revelations.

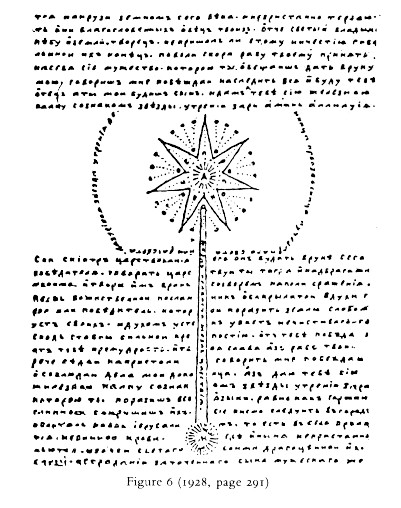

The second illustration (Fig. 6) that we will examine is found in Book 4, Article 14 of Dux i Zhizn'. It clearly shows the integration of drawing and text, as well as the extent to which the drawings are sometimes thoroughly embedded within the text. In this drawing the prescinded outer circle of the design is incomplete because it collides with both the upper and lower bodies of the main text. The lower portion of the circle has been flattened and rests upside-down against the lower section of the main text. This circular design is formed by text which announces that the sky-blue Morning Star proclaims the radiant dawn. Placed within the circle of text is a design that suggests the same Morning Star. At the center of this design is the letter "D" serving as an index of Dux, "Spirit." Emanating from this character are lines representing the force of the Spirit. These lines form a circular pattern which is further reinforced by a circle of dots. From the circumference of this outer circle of dots project seven equally spaced "horns" or triangles, each containing a letter. The circle motif is again continued by the three dotted lines that move outward from the tiny circles set between each of the horns. This circular pattern is then completed by the addition of the circle made up of text. Extending downward from the star is a rod which thrusts itself into the main body of the text. The rod buries itself to a depth of fifteen lines before culminating with a circular arrangement of lines radiating from the letter "M, " the first letter of Maksirn. This perpendicular rod iconically represents the connection between the upper character for Spirit and the lower character which stands for Rudometkin; it indicates a direct link between the celestial and the terrestrial planes. Upon the rod is written "The rod of justice, the rod of Kingdom." The letters contained within the seven horns indexically represent the seven gifts which God bestows upon the future Messiah; the source for this are passages from Isaiah (11: 1-3): "But a shoot shall sprout from the stump of Jesse, and from his roots a bud shall blossom. The spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him: a spirit of wisdom and understanding, a spirit of counsel and of strength, a spirit of knowledge and fear of the Lord, and his delight shall be the fear of the Lord." (These gifts are actually six not seven, since the last two are, in reality, the same. Both the Septuagint, used by Russian Orthodoxy, and the Latin Vulgate substitute piety or devotion for the first "fear of the Lord" hence the phrase "seven gifts of the Holy Spirit.") The significance of the seven small circles placed between each of the "horns" is found in two passages in Revelations. In his letter to Sardis, John prefaced Christ's message with these words: "Here is the message of the one who holds the seven spirits of God and the seven stars . . ." (Rev. 3:1). Rudometkin's illustration utilizes both of these seven-fold images in its circular pattern. The exact meaning of the seven stars is found in an earlier passage of Revelations: "The secret of the seven stars you have seen in my right hand, and of the seven golden lampstands is this: the seven stars are the angels of the seven churches, and the seven golden lampstands are the seven churches themselves." (Rev. 1:20) In its entirety, the illustration in Figure 6 represents a movement from Isaiah's description of the expected Messiah, to the description of the Second Coming in Revelations, and finally to Maksim Gavrilovich Rudometkin. Isaiah's description of the Messiah states "He shall strike the ruthless with the rod of his mouth" (Isa. 11:4). This phrase has been adopted by John, where the Son of God is given the power to "rule them with an iron scepter and shatter them like earthenware" (Rev. 2:28). ''In the verse which follows, the Son of God says that he will give the Morning Star, the symbol of power and of Resurrection, to those who prove victorious. In the body of text that surrounds the drawing, Rudometkin para-phrases Revelations when he writes that "the One who sits upon the throne says unto me: I shall give him a rod of iron with the symbolic morning star of the breaking dawn." In both his illustration and text, Rudometkin has combined the two elements of the Iron Scepter and the Morning Star. The verbal metaphors of Isaiah and John have, thereby, been transformed into a literal, visual icon. The incorporation of this visual icon into the text makes the text itself its content more significant, more divinely inspired, as it were. Making the word into a visual image breaks through the arbitrariness of the word as a sign. This diagrams the moment of prophetic inspiration itself, which combines vision and word. The body of text which surrounds the base of the iron rod identifies this drawing as the "Scepter of the Conqueror." In addition, it also identifies, in a special language known only to Rudometkin and his initiates, the name of the New Jerusalem of Revelations as Obleetan. We have already mentioned that the phenomenon called glossolalia, speaking in tongues, is an important part of Prygun Molokan tradition. With regard to the writings of Rudometkin, however, another term, xenoglossia, is perhaps more appropriate. Xenoglossia, a term invented by a student of psychic phenomena named Charles Richet, describes an act of glossolalia wherein the subject believes that his utterances are, in fact, meaningful statements in a foreign language. William Samarin [descendant of Pryguny] points out that "what makes this belief religiously significant is that these languages were languages unknown to the speakers; they were participants in a miracle. If glossolalia is a sign, then xenoglossia is God adding to the impressiveness of the sign" (Samarin 1972:109). Much of the special language employed by Rudometkin in his writings is believed by his followers to be just such an example of xenoglossia; it is, in other words, a representative part of an entire "heavenly" or "angelic" language which was spoken by Rudometkin as Car' Duxov [Tsar dukhov], the King of Spirits. While the listeners do not understand the words it is, after all, a religious language delivered in a foreign language which is understood only by the priest or prophet their acceptance of the language forms a covenant between them and the speaker which sets them apart as initiates. Figure 4 (and its "professional" rendering, Figure 3) shows some similarities with the Russian folk art form known as Lubok.

Originally a type of woodcut print, Lubok is noted for its

simplicity of design, combination of depiction and explanatory text,

the use of text within the design itself, and the frequent clothing of

Biblical or historical subjects in native Russian costume in order to

appeal to a mass audience. This form of broadside had wide currency

among the lower classes throughout Russia for nearly two centuries,

from approximately 1650 to 1850. It is worth noting that the schismatic

Old Believers had utilized this artform to disseminate their own

religious beliefs. Although most of Rudometkin's drawings are, in our

judgment, not derivative, Figure 4 does show some Lubok similarities.

In this drawing, known as "The Woman Clothed in the Sun," the central

female character is garbed in the traditional utilitarian dress of the

Russian peasantry. She represents the Prygun Church itself as the Bride

of the Lord. Her costume consists of the standard three elements for

female dress: a [triangular]

head

scarf (kosinka), a two-piece skirt (jub) [iubka] and blouse (kofta),

and

an

apron

(fartuk) (Moore 1983:191). Rudometkin has clothed her in the sun by surrounding her with rays of light and an outer circle comprised of more text. This text reads from the bottom left around the circumference of the circle and advises the reader to look to the ways of the righteous, God's people, for edification. The text placed above and below the circle of the sun states that "so sayeth Zion. My God and my light. This light of mine will be known throughout the universe. This circle is my virtue. I am the living way of the word." Rudometkin explains that she is the Apocalyptic wife, the Bride of the Lamb from Revelations, and that "the sun is the true Christ and his shining on her is the Holy Spirit" (M.G. 4; 13:40). She represents the faithful of Zion and their wedding with God after the Apocalypse "Our church is the one that is clothed in the sun." (M.G. 3; 7:1) Some of this symbolism is obscured in the 1915 redrawing (Fig. 3). The decolletage replaces the iconic representation of Isaiah's metaphor with inappropriate eroticism. The circle consisting of a line of text is given a border line that destroys its metastability. The whole figure is removed from the text from which it seems to directly emerge in the manuscript, and separated as an illustration accompanying the text. III. Semiotic properties of inspired illustration Semiotically, perhaps the most interesting property is the integration of text and illustration as a single creative process. In this, Figure 6 is especially significant. Note that the drawing is not merely appended to a text, nor is a text worked around a preexisting drawing. The textual material in the lower half makes room for the descending shaft of the scepter, while the circle of text surrounding the top of the scepter is flattened as it runs into the top line of the writing. In this regard, compare the professional rendering from the 1915 edition (Fig. 5) with Rudometkin's original in Figure 6. In the redrawing the scepter is pulled out of the text and is presented as an accompanying illustration. The circle which consists of words in the original is provided with a defining border line, but its engagement with the writing on the top and bottom is lost, and the gap at the bottom is unmotivated. It separates what the original inspired drawing had united. Another property of these illustrations is that letters, words and phrases are integrated within are part of the drawings, and as metastable figures help form the drawings. We noted this especially in regard to Figure 1.

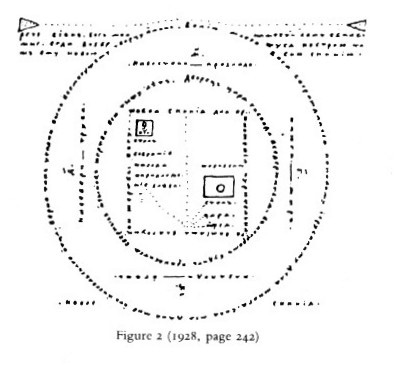

Another illustration (Fig. 2) which we cannot explicate in detail here, represents the floor plan of the New Tabernacle on Mount Zion, and consists almost entirely of phrases serving as metastable figures. In other drawings, such as Figure 6, initial letters are used as indexes for names or titles. With regard to this property, there is a fascinating similarity between Rudometkin's illustrations and some of e. e. cummings' poetic experiments. Cummings' "visual iconicity" is discussed by Richard Cureton. This also involves the use of letters and phrases as metastable forms. Like the S&L-user Molokan drawings, these experiments seek to convert the arbitrary the normal written/visual code of language into a non-arbitrary, better, iconic, sign system. There is also one very amusing quotation in the Cureton article. He cites a critic, R. P. Blackmur, who called the "eye-poetry" of e.c. cummings "a sin against the Holy Ghost" (Cureton 1986:250). One wonders how Blackmur would react to Rudometkin's anointed palm tree, which Rudometkin believed was produced through the insiration of the same member of the trinity! Another property is more tentative the absence of purely decorative marks in the drawings. In principle every stroke is a sign. The lines and circles that at first seem purely decorative actually represent rays, stars, and so forth. This is not an absolute property. The Lubok-like drawing, Figure 4 (and another not reproduced here which depicts the whore of Babylon), may be somewhat exceptional note the decorative lines in the clothing. We suggest that these properties enhance the drawing as a

focus for pious reflection. The use of writing in forming figures

invests the word with a non-arbitrary deeper significance. The

metastability of the figures using text serves to focus and draw in the

disciple's attention. Unlike conventional illustrations which may

present information otherwise not conveyed in the text, these drawings

diagram the text itself, in some cases (as in Fig. 6)

condensing a great deal of textual information into an image that may

be contemplated. Using images for "pious

reflection" with "deeper significance" apparently returns S&L-users

back to whence they came, with these icon-like images, saint-like

Maksim, religious dress, rigid rituals, etc. The S&L-user elder

prophet, Fred Slivkoff, now in Australia, often quipped: "We left

Russia to flee the Orthodox Church, and created our own Orthodox Church

in America."

Back

to

Molokan and Prygun NEWS 2003

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||